The @import() builtin is how you use code from outside your file. A string literal is given as an argument and this is either a relative path to another file or an arbitrary string configured to represent a package. An important detail here is that the path case cannot reach above the root file, so let’s say we have the following filesystem:

map.zig

src/

main.zig

bar.zig

parser/

http.zig

foo/

blarg.zig

If your root file was src/main.zig, it could not import map.zig or foo/blarg.zig, but src/parser/http.zig could import src/bar.zig by doing @import("../bar.zig") because these are within the root’s directory.

The special case for package strings that you’re familiar with is “std” which the compiler configures for you automatically. Some examples of imports:

const std = @import("std"); // absolute classic

const mod = @import("dir/module.zig"); // import another file

const bad = @import("../bad.zig"); // not allowed

const pkg = @import("my_pkg"); // package import

The other major detail here is that @import() returns a type – I like to visualize

const mine = @import("my_file.zig");

as:

const mine = struct {

// contents of my_file.zig:

// pub const Int = usize;

// ...

};

And now you can access Int via mine.Int. This is leads to a cool pattern where a file cleanly exports a struct by simply declaring members of a struct in the root of a file:

const Mine = struct {

// contents of MyFile.zig:

// data: []const u8,

// num: usize,

// ...

};

The convention here is to use CapitalCase for the filename.

Packages

Packages are ultimately communicated to the zig compiler as command line arguments, I will leave it to the reader to research --pkg-begin and --pkg-end on their own. Instead I’ll demonstrate what manual package configuration in build.zig looks like – at the end of the day, this work is done for you by the package manager.

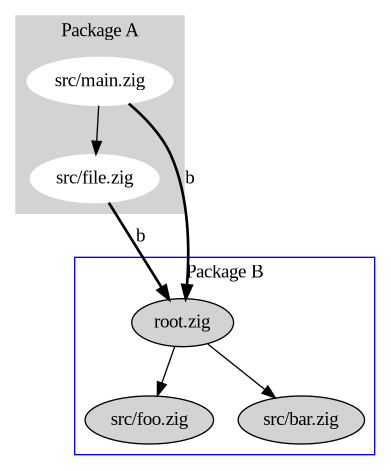

Every package is made up of one or more files, with one of them being the root. All these files are connected through file imports, and any package imports refer to the root file of another package. In the following figure we have package A and B, made up of (src/main.zig, src/file.zig) and (root.zig, src/foo.zig, src/bar.zig) respectively, and the files in package A import B. Package imports are bold arrows with a label corresponding to the string used in @import().

If we wanted to use package A in a program we wrote, we would have the following in our build.zig:

const std = @import("std");

const Builder = std.build.Builder;

const Pkg = std.build.Pkg;

const pkg_a = Pkg{

.name = "a",

.path = "/some/path/to/src/main.zig",

.dependencies = &[_]Pkg{

Pkg{

.name = "b",

.path = "rel/path/to/root.zig",

.dependencies = null,

},

},

};

pub fn build(b: *Builder) !void {

const exe = b.addExecutable("my_program", "src/main.zig");

exe.addPackage(pkg_a);

}

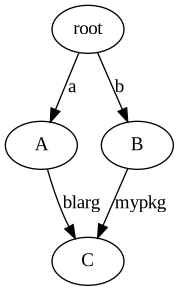

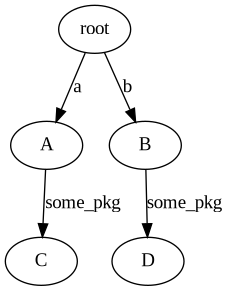

So in order to use A, you need to tell it where to find “b”, and this is nice because it is trivial to drop a different implementation of package B. The configuration for “b” only counts inside files belonging to package A, we will not be able to import package B in our program, to do that we would need to explicitly configure that relationship with another call to addPackage(). Each package has its own import namespace and this allows for situations where different packages import the same code using different import strings:

and it allows for different packages to be referenced with the same string:

This makes for a simple and consistent medium in which to perform package management, where package resolution, replacement, and upgrading challenges are more about user experience rather than technical feasibility.